“I will convince you that it’s beautiful. That’s my job.”

Eduardo Sicangco dislikes “existential” questions about art and artistry. He rolls his eyes and sighs impatiently, casting about for release from such torture. He’d much rather talk about the heavy gleaming chandelier he’s been eyeing in the foyer, or his recently purchased African lovebirds, or the iridescence and elusiveness of dragonflies.

Eduardo V. Sicangco descends the central staircase in Stephen’s at Balay Puti in Silay City, Negros Occidental.

It’s not that he has no answers to such questions, but that he prefers to dwell in the concrete world of forms, shapes, and colors that he can mold and manipulate into his glittering creations. Sicangco is a man who resists the airy abstractions that underpin his work because he knows the tangible world is where things get done.

He arrives early for his interview, scurrying into Stephen’s at Balay Puti with an air of distracted enthusiasm, tall, imperially slim, dressed casually but neatly in a crisp button-down and jeans. There’s an elfin cast to his face and a sly twinkle in his eyes, which observe the interview team warily. He greets everyone in his sonorous baritone, with a throaty chuckle softened by a lifetime of cigarettes and scotch. None of this hints that an internationally acclaimed stage designer has just entered the room.

The timing is fortuitous—he’s slipped into town for a few weeks, his first visit home since the pandemic started, and it aligns perfectly with the Negros Season of Culture tribute to his life and work. And yet even this raises his eyebrows. “I’m not dead yet,” he booms, insisting that he not be the subject of a hagiography, or a eulogy.

But the tone of assessment, of stock-taking, can hardly be avoided. At this point, he has been continuously designing scenery and costumes for over half a century for practically every kind of theatrical spectacle possible, on Broadway and far off it—plays and musicals, operas and ballets, even films and circuses. Throughout his career, he built a reputation for exacting professionalism and consummate craftsmanship, becoming the go-to man whenever productions called for glitz, glamor, and sensational opulence.

Eduardo V. Sicangco works on a costume design sketch for a recent Pioneer Theatre Company revival of the popular musical Hello Dolly! in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“I can’t define what an artist is; I just am,” he protests. But once he gets past the absurdity of the question, the words come tumbling out. “The artistic sensibility, I believe you’re born with. The main thing I look for in an artist is curiosity, and joy, and tenacity. Grit. ‘Cause god knows you don’t make a lot of money doing art. But we don’t do it for that anyway. I mean, I do it because I—I have to do it, you know? It feels great.” He elaborates further: “What’s beautiful to me might not be beautiful to you, but it’s my job as a designer to convince you that it’s beautiful. That’s my job.”

His friends call him Toto, the nickname and epithet for young boys, this middle child of the Varela-Sicangco clan, he who was singled out early on (That one!) by his mother, soprano Nena Sicangco, as having a touch of the artist. She signed him up for art lessons with local artists and took him behind the scenes of her performances, showing him how the magic and illusions of the stage were constructed. “Serious damage,” he drawls. “Goddamn, serious damage, I say. Mom knew.”

Irreversibly smitten, he went on to apprentice under future National Artist for Theater and Design Salvador Bernal, designing sets and costumes at the Cultural Center of the Philippines for Ballet Philippines. Having attained what for many would have been the pinnacle of their career, Sicangco craved broader horizons. He decamped to New York City to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree at Tisch School for the Arts, and has lived and worked on that side of the world ever since.

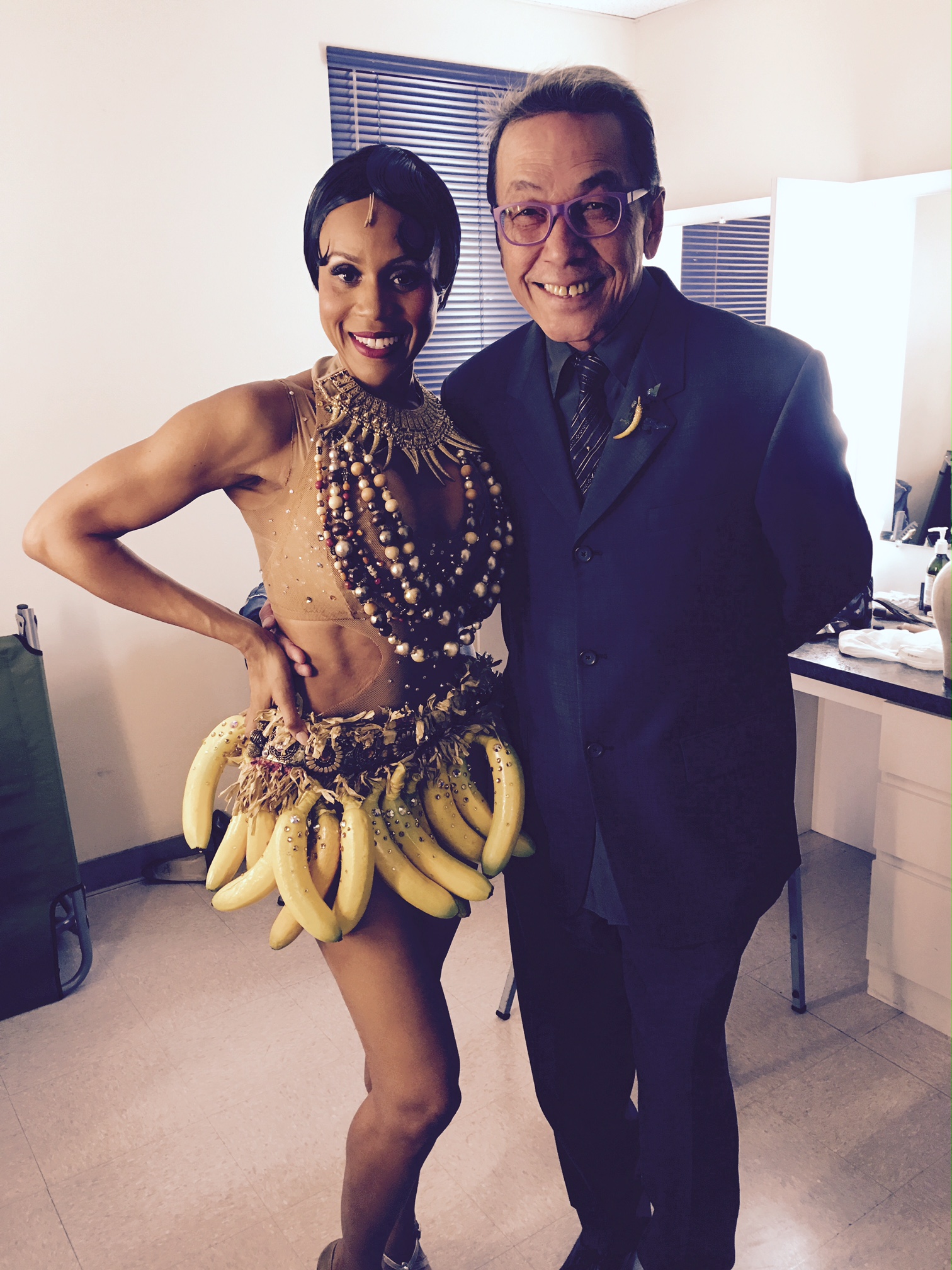

Eduardo V. Sicangco poses backstage with Deborah Cox, star of the 2016 musical Josephine by the Asolo Repertory Theatre in Florida, USA.

“I could never have achieved what I’ve achieved by staying here,” he muses. “I really wanted to learn, to perfect my craft, and that’s why I applied, and that’s why I stayed in New York.”

He betrays some guilt at choosing to work on the other side of the planet instead of home. He maintains that work such as his could never thrive in a country in which the arts are accorded secondary status only begrudgingly, if at all. “I admire very much those who stuck to it. I was just selfish when I left, yes, but not that selfish. Design needs a lot of support. Not just in terms of artisanal support, but also budgets.”

In his analysis, the problem is economic, more than a distaste for arts and culture. On Broadway or the West End, massive budgets are allocated to shows in the hopes of creating a hit like The Phantom of the Opera, or Chicago, or The Lion King, which could potentially run for decades and guarantee steady income for all those who work on it. This promise attracts the best talent, whether onstage or behind-the-scenes, who perform at the highest levels to ensure success.

In the Philippines, designers do their best with what’s apportioned, working within the means provided. Producing excellent work under such conditions isn’t impossible, but it ironically perpetuates the problem. “Because you’re an artist, and because hopefully your standards are high, you kill yourself to make it look good,” Sicangco explains. “So when you make it look good, and it looks good, producers go, ‘Puede pala.’” Thus design budgets continue being miniscule, and the cycle carries on.

Cinderella arrives at the ball in this scene from a 2009 pantomime version of Cinderella by the Childrens Theater Company in Minneapolis, USA. Sets and costumes by Eduardo V. Sicangco.

To make ends meet, local designers often take on any kind of design work outside theater and film—weddings, corporate events, etc. Sicangco isn’t above such projects. “It’s called show business, not show art,” he says. “Survival. That’s creative too.” But he is clear-eyed about the career decisions he made. “It takes a village to raise an artist. I don’t want to be Joan of Arc; I can’t. ‘Di ko kaya. Sure I want to share; sure I want to up the level. But that’s a lot of work.”

Then he turns his eye to Negros Occidental, and Bacolod City. “Let’s see what this new administration will hopefully try to accomplish with regard to the arts,” he says. “With every new administration you hope for a silver lining, in terms of support for the arts.” Having come of age as a theatrical artist in Bacolod City, Sicangco knows whereof he speaks. “Haven’t we needed a theater, other than the Gallaga Theater, for the longest time?” He cocks a sardonic eyebrow. “I’m talking governmental support. Grants. The talent has always been here. Always. But undeveloped. It’s in our DNA.”

He has vivid memories of what he refers to as the “Bacolod Renaissance” of the 1960s, when his parents’ generation were culturally animated by the Lions Club, which regularly produced theatrical spectacles that sparked his imagination, and by young La Salle Brother (and art lover) Alexis Gonzales, who collaborated with the club and organized a theater group in La Salle College. Sicangco joined the Genesius Guild and there found his footing on- and offstage. “We were a bunch of kids,” he recalls. “We put up plays every summer in the Speech Lab, which is now called the Gallaga Theater, just for the heck of it. Because it was fun.”

Original sketch of a costume design by Eduardo V. Sicangco for Fruma Sarah, a character in the musical Fiddler on the Roof, done for a never-completed Negrense production.

He credits his upbringing in Negros Occidental for his success as a designer. “You are formed, you are totally formed by where you grew up,” he says. When pressed to identify what it was about Negros that informed his artistry, he adds “because of the exposure to a high level of taste, maybe? And sophistication, which is what Negros is known for.”

Sicangco grew up amidst the postwar prosperity of the Negros sugar industry, when Negrenses were a cosmopolitan bunch with ready access to fine art and culture all over the world. The exposure to local and foreign influences fed into his creative well, from which he freely draws as the need arises. “Some plays call for minimalism, because it’s about telling the story. Other shows, like an ice show or a Vegas revue, you’re paid to show off. That’s your job description: Dapat bongga. And that’s where the Filipino comes out.”

His Filipino background, with its melange of cultures and its fiesta mentality, gives him a versatility other designers could only dream of. “I hate it when people say our culture is not original because it’s a mix of Spanish, American, Oriental,” he argues. “But that’s our culture. And as a designer, god, it’s amazing to have that in you.” Having grown up in such a polyculture, switching between and fusing European and Asian elements in his work comes naturally. “That was luck, and I embrace that.”

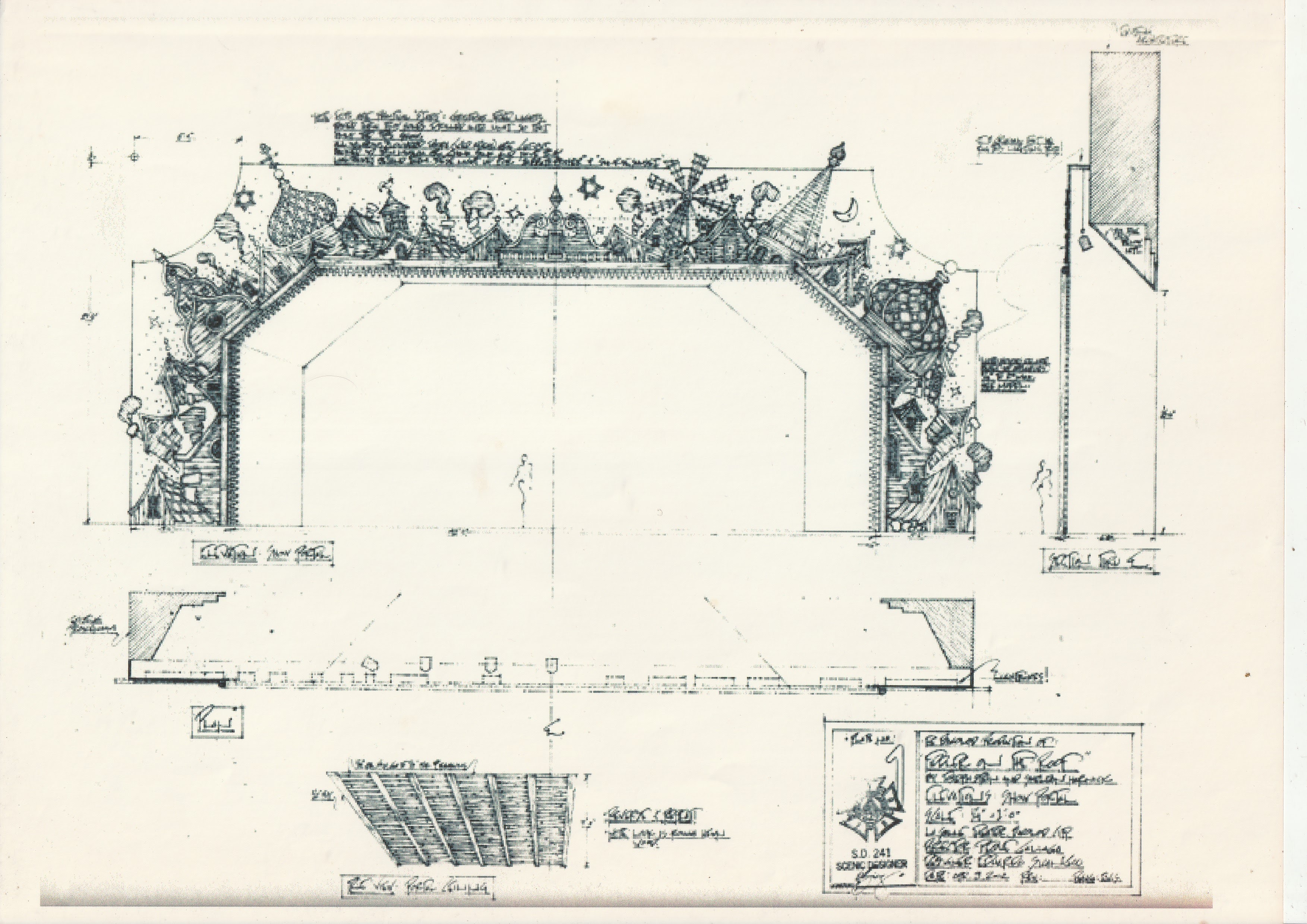

Original sketch rendering by Eduardo V. Sicangco of the proscenium arch for a never-completed Negrense production of the musical Fiddler on the Roof .

A quick glance at Sicangco’s resumé reveals his range. He’s worked on musicals like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, The Man of La Mancha, Brigadoon, The Rocky Horror Show, Peter Pan, and The Sound of Music; as well as operas like La Traviata, Carmen, The Barber of Seville, and Die Fledermaus; ballets like Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, and The Nutcracker; and plays like The Royal Hunt of the Sun and Les Liaisons Dangereuses. He designed costumes for The Rockettes, Siegfried and Roy’s Vegas show, the on-board musical shows of Royal Caribbean International cruises, and Walt Disney’s World on Ice. He designed three editions of The Greatest Show on Earth by the Ringling Brothers/Barnum and Bailey Circus. He’s created sets and costumes for Dolly Parton’s Dollywood Entertainment extravaganzas and the sets for five iterations of the risqué charity show Broadway Bares. Murals he designed ended up onscreen in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club and Adrian Lyne’s Lolita, and he provided concept art for the Jet Li/Jackie Chan starrer, The Forbidden Kingdom.

In the end, despite his considerable success abroad, working alongside some of the biggest names in showbiz, the productions he’s proudest of are also the most personal. He describes the joy and satisfaction of taking a bow in 1997 beside his sister, prima ballerina Cecile Sicangco, at the end of a ballet he had designed, in front of their mother at the CCP. “How magical is that?” He smiles at the memory. “That was the highlight of my career. We took a double bow, and I looked at Mom, and the smile on her face… Full circle! We were her creation.” He lives for moments like these far more than the twinkling lights of Broadway. “Life is simple,” he says. “The older you get, the simpler it is. But you have to go through the whole ordeal to get to the simple stuff.”

And then, catching himself becoming a little too philosophical for comfort, he reverts to the real world again. “The really interesting thing about my career,” he says, “is I’ve done everything else except for the one thing I want the most: a long-running Broadway hit, so I can retire.” And unbidden, the philosophy returns: “Maybe that’s a good thing that you’re still aspiring toward something, ‘cause it keeps you going? But it doesn’t matter. I’ll just keep going. I like it too much.”

Text By: Vicente Garcia Groyon

Photos and Video By: Grilled Cheese Studios

Design and Architecture

Cultural Experience

Art and Craft

Food

People

BAO

-

Negros Season of Culture

Rooted. Taking on the World.

A global messaging system that promotes the cultural assets of Negros as shaped by its rich heritage and traditions, the unique identity of the place, and the talent of its people.

Popular Posts

Give Us Our Ginamos

Friday, December 08, 2023

The Heart of Art in Bacolod: How La Consolacion College Bacolod Moves Students to Dream in Color

Saturday, February 21, 2026

Chicken Ubad with Monggo (Chicken with Banana Pith and Mung Beans)

Thursday, July 15, 2021

Rooted. Taking on the World.

Negros Season of Culture is a global messaging system that promotes the cultural assets of Negros as shaped by its rich heritage and traditions, the unique identity of the place, and the talent of its people.

Search This Site

Quick Links

People

Design and Architecture

Upcoming Events

Art and Craft

BAO

Food

Menu Footer Widget

Rooted. Taking on the World.

A global messaging system that promotes the cultural assets of Negros as shaped by its rich heritage and traditions, the unique identity of the place, and the talent of its people.

Search This Site

Upcoming Events

Negros Season of Culture Celebrates National Heritage Month

Negros Season of Culture Celebrates National Heritage Month

The Negros Season of Culture Celebrates National Heritage Month this... Negros Season of Culture joins the National Commission on Culture and the Arts in celebrating National Heritage Month

Negros Season of Culture joins the National Commission on Culture and the Arts in celebrating National Heritage Month

Negros Season of Culture joins the National Commission on Culture...

Menu Footer Widget

• Copyright © -2021

- Negros Season of Culture